The authoritative Swiss Rambles reviews the accounts of Juventus. 2019/20 accounts cover a COVID impacted season when they won the league (for the 9th year in a row), but were eliminated in the Champions League last 16 by Lyon.

The loss before tax widened from €27m to €82m (€90m after tax), as revenue fell €88m (18%) from €494m to €407m, partly offset by €43m (13%) wages cut from €328m to €284m and profit on player sales rising €40m to €167m, though non cash flow expenses were up €48m.

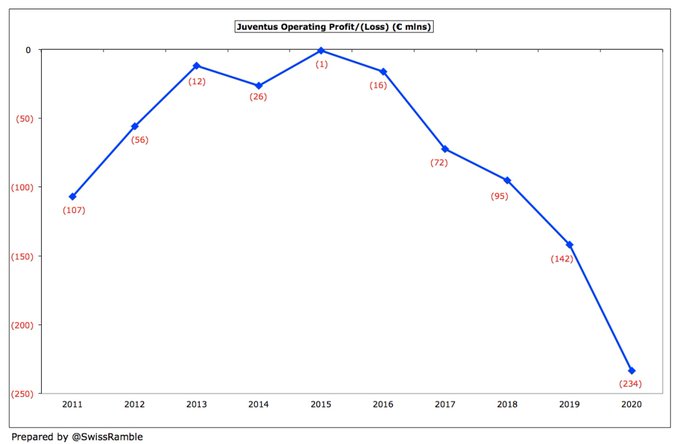

So after four years of profits, the club have now reported losses three years in a row, aggregating a €119m deficit over that period. However, the club is no stranger to losses, having racked up €151m between 2011 and 2013. They forecast that 2020/21 will end in another loss.

Driven by COVID, all revenue streams fell, including broadcasting, down €40m (19%) to €166m, and match day, down €21m (30%) to €49m. Commercial only fell €1m to €186m, as new sponsorships compensated for lower merchandising sales. Player loans down €25m to €5m.

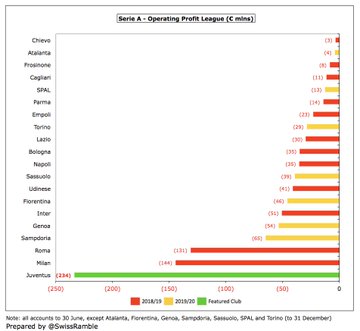

The €82m loss before tax is 2nd highest in Italy, only surpassed by Milan’s €143m, though this is a bit misleading, as other clubs’ results are from the previous season, so unaffected by COVID.

The profit on player sales increased from €127m to €167m, the highest in Italy by far, largely from the sales of Pjanic to Barcelona, Cancelo to Manchester City, Kean to Everton, Can to Dortmund, Muratore to Atalanta and Mancuso to Empoli.

Profit on player sales is increasingly important for Juventus averaging €132m a year over last 4 years, compared to only €22m in the preceding six years. No major sales to date in 2020/21, though summer window runs to 5th October this season and January window still to come.

Excluding player sales, revenue fell €88m (18%) from €494m to €407m in 2020. Despite last season’s decrease, revenue has still grown by €56m (16%) in the last four years, almost entirely on the commercial side €83m, though broadcasting is down €29m.

The €407m revenue is highest in Italy, €37m more than closest challenger Inter €377m, followed by Roma €236m, Milan €228m, Napoli €217m, Atalanta €141m & Lazio €124m. All other Serie A clubs are below €100m. Gap will grow as others release COVID impacted accounts.

It is imperative that Juventus do well in the Champions League to boost their broadcasting income, as the TV rights in Serie A are relatively low. Indeed, there were big increases in England and Spain in 2019/20, and France to come in 2020/21, while Italy is unchanged.

The Swiss Ramble estimates that the club earned €87m from the Champions League after going out in the last 16, lower than prior season’s €96m, when they reached the quarter-finals. Worth noting the influence on Champions League money of the UEFA coefficient payment (based on performances over 10 years), where Juventus has the 6th highest ranking of clubs competing this season, guaranteeing them €30m.

The Champions League is extremely important for Juventus, who have earned an impressive €449m from Europe in last five seasons. Not only is this much higher than other Italian clubs (Roma €255m, Napoli €246m, Inter €117m), but best in Europe (next highest Real Madrid €418m).

Commercial income fell slightly (1%) to €186m, as new sponsorship deals, up €21m (19%) to €130m, offset reductions in merchandising and museum/stadium tours. Highest in Italy, €20m ahead of Inter €166m, then a big gap to Milan €76m, Roma €55m and Napoli €45m). Commercial growth linked to Ronaldo’s arrival, which Andrea Agnelli said, “brings us worldwide profile”.

The increase in sponsorship deals is vital if they want to financially compete with the leading clubs in Spain, England, Germany and France, as their commercial income is much higher, e.g. five clubs were well above €300m in the 2018/19 Money League.

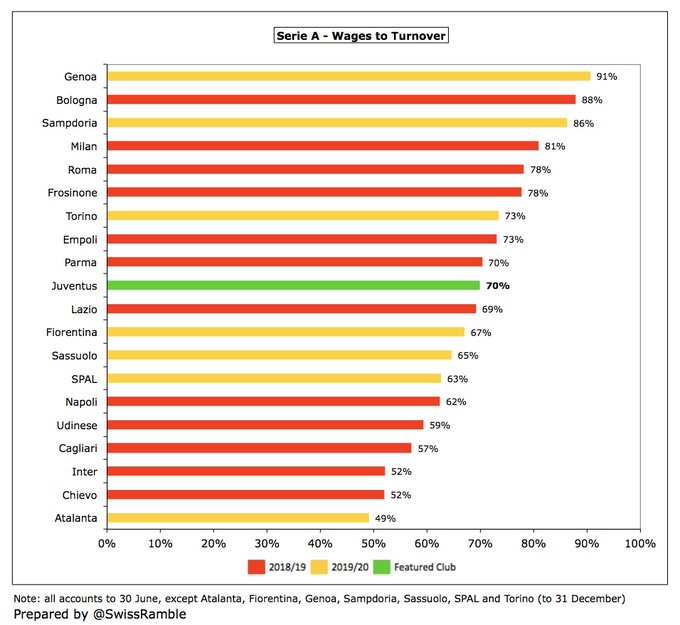

The wage bill was cut by €43m (13%) from €328m to €284m, largely because players and coaching staff gave up four months’ salary (March to June) worth €90m. The implication is that without this gesture (due to the pandemic) wages would have risen €47m to €375m.

Despite this cut, wages have still grown by €63m (28%) since 2016. The only other Italian clubs that have grown by a similar amount are Inter €68m and Napoli €50m, though the wage bill of €284m is still significantly higher than the rest of Serie A. The closest challengers are around €100m lower: Inter €193m, Milan €185m and Roma €184m. Furthermore, they might also have cut in 2019/20 due to COVID pressures. They might have also reduced wages in the same way as Juve in 2019/20.

Comments

Post a Comment